|

|

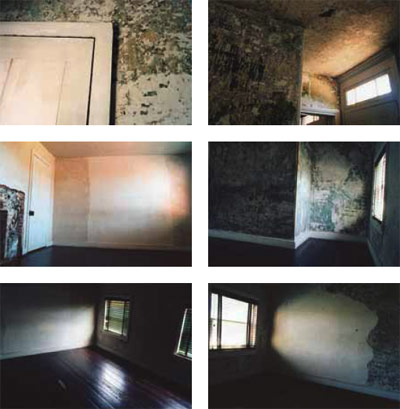

Photographs by Adam Marnie | |

|

|

|||

The Poe House tour explores the empty space of the house as well as phantom black cats, the walled-in window, and surprise-whispers revealing Poe’s continuing presence. The glory of man, and something more than his glory, is to waste his powers on the void… Thus it would seem that the history of thought can be summarized in these words: It is absurd by what it seeks; great by what it finds. “I do not wish to fill the Poe House with facts, or ideas. Nor

something

more than facts and ideas, only to keep the empty house empty and open

to possibilities.” With these words I began the Empty House Tour

of the

Edgar Allan Poe House in Philadelphia. The Empty House Tour lasted for

two weekends and was part of a series of events called “The Big

Nothing,”

sponsored by the Institute of Contemporary Art in the summer of 2004.

The Poe House, located at 530 and 532 North Seventh

Street, is actually

two houses that have been combined. Located at 7th and Spring

Garden, the site is separated by an industrial corridor at the far north

edge

of Center City. Directly up the block on Spring Garden is Robert Venturi’s

self-consciously ugly and ordinary low-rent retirement Guild House with

its well-known GUILD HOUSE sign rendered in giant red supermarketstyle

lettering. One block north of the Poe House is a city housing project

called the Spring Garden Houses. Poe’s literal house is located

at the 532

N. 7th address; 530 N. 7th was acquired at a later date and is used by

the

National Park Service for several purposes: a visitors’ lobby,

a small screening

room, a side living room library, and Park Ranger office space.

Over a span of four months I began visiting

the house to hash out plans for

the Empty House Tour. I immersed myself in most of Poe’s forceful,

highly stylized and permanently strange tales, poems, reviews and letters.

I was grateful to the Park Rangers for their professionalism and efforts

to

show connections between Poe’s everyday life and his work. Still,

I had

some skepticism. How much could the house really tell me about Poe’s

work? And how much could the work really tell me about the house? What

was most captivating for me about Poe was not how he depicted daily life,

but how he turned so conspicuously away from the things of his everyday

life via the imagination. Still, strangely or not, I was beginning to

love Poe’s

empty house as much as the extravagant visions of his work.

... calm block fallen here on earth from a hidden disaster, let this granite at least for ever show its boundary to Blasphemy’s dark flights scattered in the future. It was difficult not to feel that Poe’s

house was in fact revealing the concealed

boundaries and clouded horizons of which Mallarmé wrote.

Elsewhere, Mallarmé also memorably describes Poe the man as “worried

and discrete.”

In addition to the

basement, Poe’s row house (aptly called a trinity)

is three

stories tall: on the first floor, the parlor and kitchen; on the second,

Poe’s

room and a small side room, perhaps his study; on the third, his wife

Virginia’s bedroom and her mother Muddy’s bedroom. Last,

there is the

unfinished basement, which is essentially the soul of the house itself.

“The National Park Service is pleased to collaborate with the ICA’s Big Nothing and with Thomas Devaney on his tour of the Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site. We do not, however, endorse the content of the tour, nor do we vouch for its historical reliability. But again, we are happy to work with Tom on his Empty House project and we hope you enjoy your time here. Please let me know if you have any questions about Poe, or the house.”When asked if there were any questions, one woman wanted to know if Andrew and I were brothers, or related. As we stood before the group, the woman went on to say how uncanny it was to see us both side by side as our features were so much alike: similar height, same build, the same brown clean-cut hair, and blue eyes. As in Poe’s tales, every detail served to feed the tour. On realizing our physical resemblances, I launched directly into a discussion of the double in Poe. He makes considerable use of doubling devices in tales such as “Fall of the House of Usher,” “The Man of the Crowd” and “The Black Cat” to name a few. Roderick Usher murders his twin sister and also kills himself. Poe’s black cat is a double of another black cat that haunts his narrator and also comes to its own horrific end. I also drew on what I believed were more explicit connections between McDougall and myself, including that we both grew up only six houses away from each other on the same block. One of the great themes in Poe is the fate of people haunted by their doubles. The central example of this is the psychologically hawkish tale of “William Wilson.” Wilson is pursued by his doppelganger (of the same name) from whom he desperately tries to escape. Poe writes: My evil destiny pursued me as if in exultation, and proved, indeed, that the exercise of its mysterious dominion had as yet only begun. Scarcely had I set foot in Paris, ere I had fresh evidence of the detestable interest taken by this Wilson in my concerns. Years flew, while I experienced no relief. Villain!—at Rome, with how untimely, yet with how spectral an officiousness, stepped he in between me and my ambition! At Vienna, too—at Berlin—and at Moscow! Where, in truth, had I not bitter cause to curse him within my heart? From his inscrutable tyranny did I at length flee, panic-stricken, as from a pestilence; and to the very ends of the earth I fled in vain. The

emerging coincidences between McDougall and myself triggered

an unexpected sensation of reading a story to find yourself in the

very story

playing out before you on the page. It was Poe, of all writers, who

exploited

such devices as a part of what he called the “totality of effect.” Yet,

the

more I thought of doppelgangers pursuing doppelgangers, the more hesitant

I felt about fully embracing the idea that Park Ranger McDougall and

I were actually each other’s doubles at all.

In the front parlor I began the tour with the following

speech: “I

wish to

keep the empty house empty and open to possibilities…” I

also addressed

the following question: why is the Poe House apt for Poe’s

work?

The kitchen is roughly a 10 x 10 foot space. Here I stood

in the center of

the room and asked everyone to form a circle around me (crude and

crowded

as it was). I asked all to turn away from me to face the walls. I

said, “I’d

like you to take this time to note and notice the walls.” When

everyone was

facing the walls I said, “A chaos of cracks surrounds us.”

We walked up the narrow middle stairway to Poe’s room.

Here I invited

everyone to take a seat on the floor facing the east wall. From my

first

encounter, I was struck by a 4 x 8 foot plastered-over section of

the wall. I

learned that there had once been a window there until an addition

was

built onto the house (I suspect that looking at a number of paintings

by the

Abstract Expressionist artists over the years may have also helped

to signal

something that might otherwise have been nothing). This luminous

plastered

middle section of the wall had the presence of a Rothko painting,

though it was more dissolved and understated than any Rothko. It

held an

almost invisible light on the surface of its smooth matte plaster.

It was like

a wide door; well, no, it was really like a big blank screen, or

a domestic

fresco. I was enticed by what I would come to call the “walled-in

window.”

After two months of ruminating on the wall I made plans to use the

space

to project an imaginary slide show, or what came to be: a make-believe

PowerPoint presentation.

— THOMAS DEVANEY is a poet and the author of A Series of Small Boxes (Fish Drum Press, 2007). Projects and collaborations with the Institute of Contemporary Art (Philadelphia) include: a performance “No Silence Here, Enjoy the Silence,” for the “Locally Localized Gravity” exhibit (2007); a collaboration with Troy Brauntuch for the “Springtide” exhibit (2005) Letters to Ernesto Neto (Germ Folios, 2005), a collection of letters written to the Brazilian artist Ernesto Neto, with an afterword by Neto. Devaney is currently a Penn Senior Writing Fellow in the English Department at the University of Pennsylvania. For the complete article purchase The Sienese Shredder #2 Back to The Sienese Shredder #2 | |||

|

Sienese Shredder Editions