|

|

|

|

|

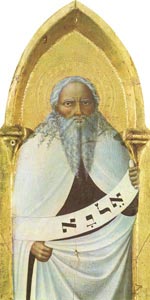

Sassetta, The

Prophet Elijah,

tempera and gold on wood,

7 1/2 x 21 1/2 inches,

Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena. |

|

|

Sassetta, Landscape,

tempera on wood,

8 5/8 x 12 5/8 inches,

Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena.

Photo credit: Scala/Art Resource, NY |

|

|

Sassetta, Landscape,

tempera on wood,

9 x 13 inches,

Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena.

Photo credit: Scala/Art Resource, NY |

|

|

Sassetta, Saint Thomas

Aquinas in Prayer,

tempera and gold on wood,

9 1/2 x 15 inches,

Museum of Fine Arts,

Budapest. |

|

|

Sassetta, Landscape,

tempera on wood,

9 x 13 inches,

Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena.

Photo credit: Scala/Art Resource, NY |

|

|

Sassetta, The Vision of

Saint Thomas Aquinas,

tempera and gold on wood,

9 7/8 x 11 3/8 inches,

Vatican Museums,

Vatican City.

Photo credit: Scala/Art Resource, NY |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Trevor Winkfield |

The Early Sassetta |

Sassetta was a painter of fragments. Or rather, as we perceive him today,

he

is a painter of fragments. The dismantling, dismembering and diaspora of

his altarpieces, together with their physical abrasions, fadings, candle

smoke stainings, restorations, excessive cleanings and varnishings have

left

us with an array of objects which can bear little relation to what people

must have seen during Sassetta’s lifetime. Posterity’s paring

of Uccello’s

oeuvre seems lenient by comparison.

Sassetta himself is a man of fragments, none of which add up to a solid

portrait. We’re in the position of those hapless archaeologists trying

to

reconstruct a vase based on slivers of crumbling handles. Sassetta is as

lost

to us as those anonymous craftsmen who erected cathedral towers. The few

biographical facts to be garnered from the archives offer little more than

a

ghost of a profile: his body is missing, the personality remains a riddle.

No

temper tantrums with Popes or severed ears can be traced to him. Like

reading shards, the profile has to be fleshed out using the surviving paintings.

(Though we should keep in mind that in all instances not only is the

painting more important than the painter, in a perfect fusion the painting

is the painter.)

It should at the outset be observed that the painter we behold today differs

considerably not only from the painter seen by his contemporaries, but

also from the painter who was first extricated from historical obscurity

a

century ago. Fascination with his work has steadily increased in relation

to

the number of art movements his reputation has been subsequently filtered

through. Transmitted via the distorting lens of Cubism, Surrealism,

Abstraction, Pop Art and Minimalism (not forgetting comic strips and

Technicolor), he now appears, along with Giovanni di Paolo and Paolo

Uccello, as one of the most idiosyncratic and yet most profound painters

of

the Quattrocento period, one of those talents with most to offer present-day

viewers and artists. (On the other hand, the cumulative effects of those

very

same movements which renewed interest in Sassetta have, by contrast, rendered

Raphael’s influence all but harmless.)

Quite literally, we see neither the spectrum nor space (let alone religion)

as our predecessors saw them during the Dark Centuries preceding

Impressionism. Sassetta has been one of the beneficiaries of the twentieth

century’s brightenings and flattenings—and, let’s note,

its parallel embracing,

absorption and abandonment of the concept of “Primitive.” As

a result,

he and his Sienese kin now feel closer to us than the Barbizon School.

“Could it be that at the center of Sassetta’s art there lay no

core of sodden

sentimentalism but an original and virile mind?” So wrote John Pope-Hennessy

somewhat uncertainly in his eximious 1939 disquisition on the artist. But

just as there has been a pictorial revolution over the past century, so

in the gap between Pope-Hennessy’s query and our own time there

has been a quickening aversion towards purely formal dissections of a

painter’s worth, a reaction to a clapped-out academic modernism, particularly

in its abstract branches.

Without a hint of embarrassment, previously squirm-inducing designations

such as “charm,” “delightful,” “mythopoeic,” “lovely,” “toylike,”

even Pope-Hennessy’s “sentimentalism” have begun to vivify—or

muddy,

depending on one’s stance—the aesthetic waters for the first

time since

Victorian days, adjectives no longer cast as epithets but as locations of

interest.

Not that Sassetta lacked classic skills in picture making: serenity, harmony

and balance he had in abundance. No mere oddball he. But his career

stands as one more riposte to the widespread belief that only formalists

have long creative lives. Visionaries too can have longevity. Today, when

individualism is a trait prized above all others, there’s another point

in

Sassetta’s favor: he looks as though he were painting for himself and

not

only for the clergy or wealthy patrons. He was painting for them, of course,

but cleverly disguised this necessity. And it—the work—was all

laid down

before the aloof cleverness of the Renaissance stiffened bristles throughout

Italy, at a time when fervid imaginations still granted improvisation a starring

role in design.

—

TREVOR WINKFIELD exhibits his paintings at Tibor de Nagy Gallery in

New

York City. Trevor Winkfield’s Drawings was recently published

by Bamberger

Books. The present text on Sassetta is the first part of a book in progress.

For more

information go to trevorwinkfield.com.

For the complete article purchase The Sienese Shredder #1

Also by Trevor Winkfield

Daubs of Late

Lubin Baugin

Back to The Sienese Shredder #1

|  |

|

|

|